|

| This is the one to beat. (Imagine a rectangle, imposed on her extreme dimensions.) |

For this reason non-rigid reference bodies are used, which are as a whole not only moving in any way whatsoever, but which also suffer alterations in form ad lib... . This non-rigid reference body... might appropriately be termed a "reference mollusc"... .

From Relativity: The Special and General Theory by Albert Einstein

BASELINE: The Design against which All Others Compete

All along, the design to beat has been some close variant of LUNA, the Bolger inspired Advanced Sharpie that was our home for a dozen years.

Any prospective candidate has to improve on her gestalt: footprint, roominess, carrying capacity, ability, ease of construction, operation and maintenance, large windows, social continuity, thermal dynamics, storage, rig possibilities, deck layouts... all of these, mushed together, embody a single, quasi-morphous reference mollusc. A baseline.

Otherwise, we'd just build her again, with the benefit of hindsight.

As I considered earlier, Curvier Dogs spike some of these qualities, vis a vis square boats, but dip in others. For the mollusc that is Anke and myself, square boats won out. Here, I want to take a closer look at why we're choosing a box barge over the equivalent Advanced Sharpie.

We believe that LUNA's design is 'improved', for the gestalt of our needs, by translating the AS to a TriloBoat. We came to this conclusion by mulling the comparisons across a number of headings:

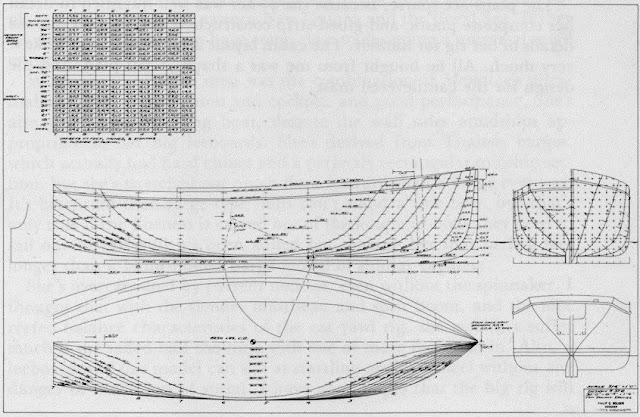

Capacity - Profile and plan view curves are formed by cutting away from the slab formed by maxLength x maxBeam x maxDraft. These cuts remove large amounts of interior volume, squeezing interior spaces and dropping almost a third(!) of potential displacement. The only way to get it back is to go deeper, wider or longer.

The barge, on the other hand, maintains full value in plan view, and merely cuts a wedge from the underside at each end. This maximizes volume and displacement on given dimensions over any competitor!

For both displacement and volume, the box barge wins by a wide margin.

Ability - LUNA was nimble (spins on a dime), and fast as her rig allows. Her only vice was rounding up in heavy winds (partially the schooner rig, but also the downside of nimble). The barge is slightly less nimble (but is harder for gusts to force into the wind).

In short, steep chop I expected the AS to sail better, but I couldn't tell the diff in practice.

The slow-but-steady form of junk rig we favor evens the playing field. Off the wind, we're not seeing any differences, and that's how we prefer to make tracks. Into the wind, AS any advantage is small.

I'd give a slim edge to LUNA.

NOTE: If better performance under our (slow) rig were a high priority, a Curvy Dog might possibly smoke 'em. But not by as much as one would suppose!

Ease of Construction - TriloBoats dominate on this score, being as near optimal as possible. Their large deadflat and preponderance of parallel lines and whole or even-fraction-of-sheet-materials radically simplifies construction. Good thing, as they've bartered away some other qualities to achieve it!

Of particular note is that AS, plan view curvature cuts across a section-of-cylinder deck, climbing its crown as the sides curve inboard. This complicates lofting/layout and requires more side material to accomodate the upward sweep of sheer. TriloBoats, with parallel sides, sidestep entirely. We'll revisit this when looking at TAB options.

The barge has a slight advantage in that flat pane glass (the real stuff, as opposed to flexy plastic) installs easily along the planar hull. An AS hull must be faired out to a flat landing. Ditto the guards.

After building, the AS generates a mountain of wasted material; the TriloBoat a very small pile. That's just money and effort down the drain.

Ease of Operation - The big, rectangular decks ease operations, big-time, and the foredeck has ample room for a high-power winch. The deadflat simplifies many on-the-beach operations.

Advantage, barge, by a wide margin.

Ease of Maintanence - Box barges, tend to have larger, interior spaces which ease access for cleaning. With more surface area, however, they take proportionally more elbow grease and paint, inside and out.

This one goes to LUNA by a nose.

Everything else is a wash between LUNA and translation. Their rigging, layout, gear and hardware are identical.

Tot it all up, and, for us, the box barge version (I'll call TLUNA from here on out) wins hands down. LUNA's advantages are slim margin; TLUNA's are wide. Curvier Dogs would certainly gain ground if we had offshore aspirations, but we don't.

For our inshore cruising needs, sharpie beats Curvier Dogs, and barge beats sharpie.

TLUNA is the one to beat.

|

| T32x8 LUNA aka TLUNA |

*****

In a previous post, we mulled over the FANCY STANDARD (FS) option, but without reference to our baseline. In fact, the baseline was always holding the fort, and I should have presented it from the git go.

Let's backtrack a bit, then, and compare TLUNA with the FANCY STANDARD (FS). Hulls are identical, so we're mainly looking at interior and superstructure considerations.

Ease of Construction - Close to a wash. Choice of window materials might sway it one way or the other, but it won't be decisive, either way.

Windows - As you may recall, those huge, glorious FS windows were ever so tempting! But with windows comes doing windows. That takes lots of water and very clean, soft rags if polycarbonate is involved (no squeegee, either). Plus, do I sound like a the kinda guy who does windows?

TLUNA has ample windows - nearly contiguous - in salon and bunk. SLACKTIDE's view is purty durn good; TLUNA's windows are the same length albeit a little less tall. But, in the PH/galley, we double down with 360deg view and again as much window length... better, even, from the counter sitting position than the FS.

Still, TLUNA is ample, but the FS gains an almost unassailable lead.

Thermal dynamics - TLUNA's galley cabin is a heat chimney. Heat rises and dissapates relatively quickly. Its windows are harder to insulate; the companionway is unclosable, ruling out accidental asphyxiation, but venting heat.

The cabin of FS has more volume (more to heat), but is a single space. Heat can circulate freely within that space, without crowding a small region of it.

I'd give the edge to FS.

The Bunk - As discussed in a previous post, the low foredeck and forward position of the FS bunk cramps its style. There are solutions, but they're not pretty.

TLUNA's bunk is positioned further aft, so is not clipped by the bow bottom curve. It has considerably better headroom, with a large hatch with good placement that doesn't interfere with deck traffic. It is fully integrated with the salon, so extends the social space and open sense of inboard spaciousness.

Solid gain for TLUNA.

Windage (related to ability) - This one is tricky. My intuition is that the FS has more. But TLUNA's decks are broken up, so turbulence may eliminate any gains. TLUNA can carry a dinghy on deck, which pretty much fills her profile in to as-much-or-more than the FS.

Being ignorant of the facts, I'd flip a coin. My guess is that it's a wash, anyway.

Rig possibilities - I'll go into these in a later post. The main point is TLUNA's shorter foredeck makes better use of the airspace above the boat... she can set more working sail than the FS.

Lateral Resistence - TLUNA can go skegs or boards, FS can ONLY go skegs (deeper draft). Of course, skegs have some advantages of their own, but at the end of the day, we prefer ultra-shoal draft.

NOTE: I did figure out a working board system for FS, with no clunking when stowed. But it's somewhat complex to construct, in comparison to the other two, and requires antifouling inside an outboard trunk. We decided, given its novelty and remote building realities, that it was a no-go.

*****

So TLUNA, our new baseline - our mollusc. It wins out against all comers. We've narrowed the field to the point that, from here on, we'll only be considering variations within this single design framework.

Stay tuned!